Platform

AI Security

AI Security

AI Observability

Solutions

Integrations

Resources

Every security tool hits the same wall: encrypted traffic. Here's how we broke through it using eBPF.

Picture this: You've just deployed a comprehensive database security monitoring system. It tracks every query, flags suspicious access patterns, and alerts on potential data breaches. Your CISO is happy. Your compliance team is thrilled.

Then you push to production.

Suddenly, your beautiful monitoring system goes dark. Zero queries captured. No alerts. Complete silence.

What happened? Production databases use SSL/TLS. Always. Non-negotiable.

And your monitoring tool? It just became useless.

Let's understand why this is such a fundamental problem.

In production environments, SSL/TLS isn't optional—it's mandatory:

Your database monitoring solution must work with SSL. There's no "we'll add SSL support later" option.

When we started building Aurva's database security platform, we evaluated every existing approach:

Option 1: MITM Proxy (The "Breaking Security to Add Security" Paradox)

The traditional enterprise approach: terminate SSL at a proxy, inspect the traffic, re-encrypt it.

Why it fails:

Companies are rightfully afraid of inline solutions. We've heard this fear repeatedly from security teams: "We can't put anything in the critical path. One bug and we take down production."

Option 2: Database Audit Logs (The "Trust But Don't Verify" Approach)

Most databases have built-in audit logging. PostgreSQL has pgaudit, MySQL has the audit plugin.

Why it's insufficient:

Option 3: Application-Level Instrumentation (The "Boil the Ocean" Strategy)

Instrument every application that touches databases. Add logging to every ORM, every database client library.

Why it doesn't scale:

For Aurva, the requirements were non-negotiable:

This seemed impossible. How do you see inside encrypted connections without decrypting them?

Here's the key realization: SSL/TLS encryption happens in user space, not the kernel.

When your application calls SSL_write() or SSL_read(), the plaintext data exists in memory for a brief moment before OpenSSL encrypts it. If we could hook those functions at the kernel boundary...

Enter eBPF.

eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) lets you run sandboxed programs in the Linux kernel without changing kernel code or loading kernel modules. Originally designed for packet filtering, it's evolved into a general-purpose observability framework.

Think of it as a virtual machine inside the kernel:

Why eBPF for SSL monitoring?

While eBPF started with kernel instrumentation, uprobes (user-space probes) extend it to user-space functions.

Uprobes let you attach eBPF programs to any function in user-space libraries. When that function is called, your eBPF program runs—capturing arguments, return values, and memory contents.

Here's the genius part: uprobes run in kernel context, so applications can't disable them. They're completely transparent to the application code.

The plan:

SSL_read() and SSL_write() functionsSounds simple, right?

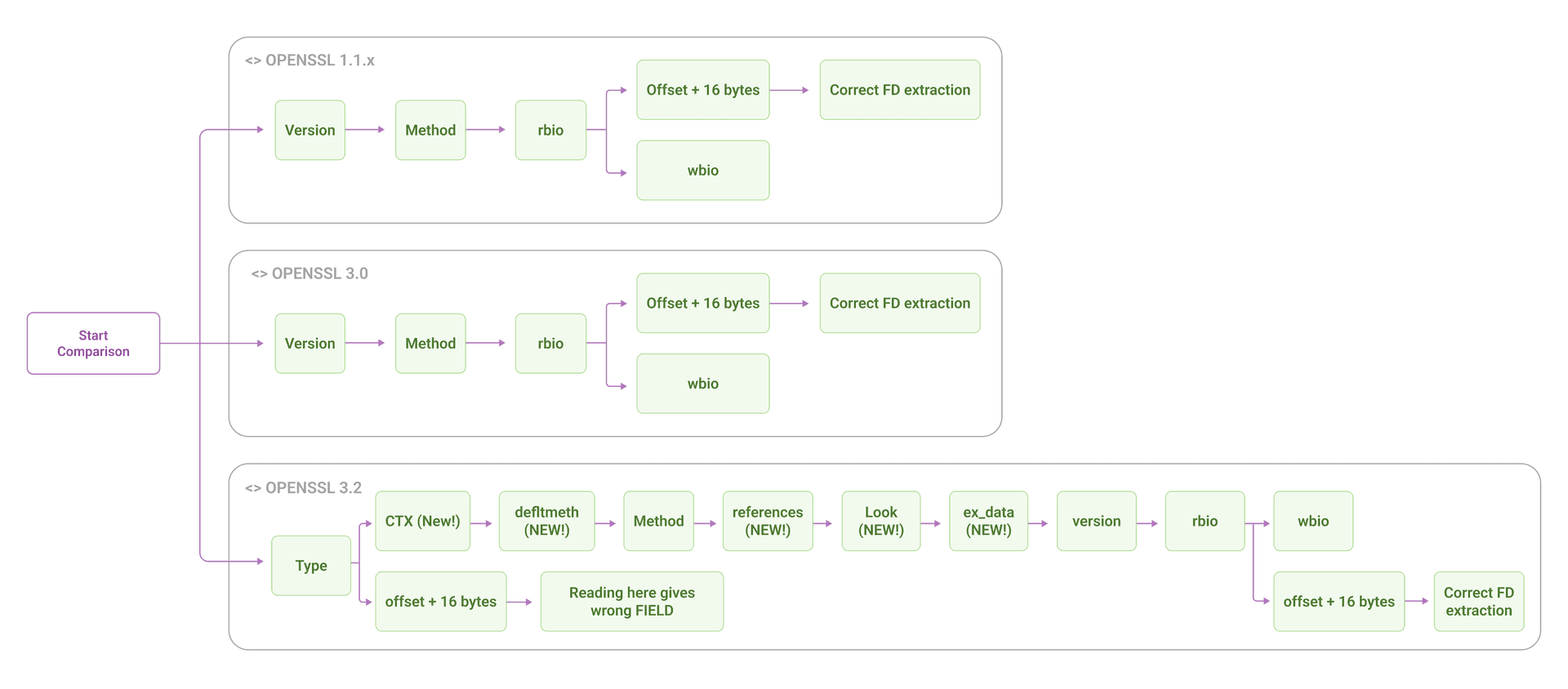

We quickly discovered the first problem: OpenSSL's internal structures change between versions. And by "change," I mean completely restructure.

To extract the socket file descriptor from an SSL connection (so we can correlate encrypted traffic with actual network connections), we need to traverse OpenSSL's internal SSL structure:

SSL context → BIO structure → socket FDOpenSSL 1.1.x has a simple 4-field structure:

SSL {

version

method

rbio → points to Read BIO → contains socket FD

wbio → points to Write BIO

}OpenSSL 3.0 restructured the BIO:

BIO {

libctx ← NEW FIELD!

method

callback

... 6 more fields ...

num ← The FD we need, now at a different offset

}OpenSSL 3.2 added seven fields to the SSL structure:

SSL {

type ← NEW!

ctx ← NEW!

defltmeth ← NEW!

method

references ← NEW!

lock ← NEW!

ex_data ← NEW!

version

rbio ← Offset shifted by 56 bytes!

wbio

}OpenSSL 3.5 added another field before version.

Each version change shifts the memory offset of rbio and wbio. If we use the wrong structure definition, we're reading random memory and extracting garbage file descriptors.

The consequence: Silent data loss. No errors. No warnings. Your monitoring system just... misses events.

(See OpenSSL's ssl_st structure history for the gory details.)

Here's where eBPF's safety restrictions become a problem. The eBPF verifier enforces strict rules to guarantee kernel safety:

You are restricted to:

OpenSSL_version()malloc(), no dynamic allocation at runtimeSo we can't just call OpenSSL_version() and branch on the result. We need to handle multiple versions in the same eBPF program, using only the tools the verifier allows.

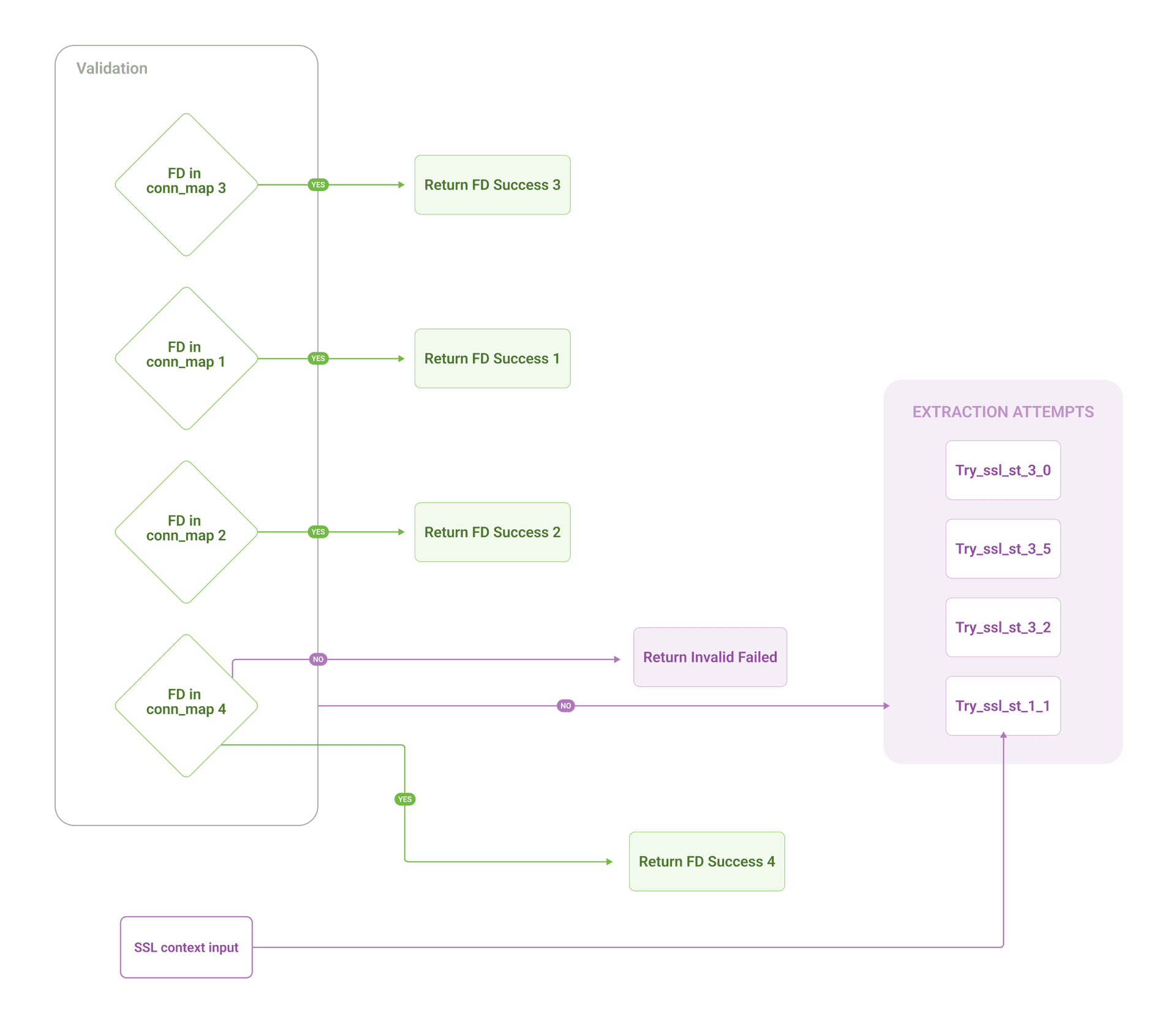

Our approach: Define all known structure layouts and try each one, validating against kernel state.

get_fd_from_ssl_context(ssl_ptr) {

// Try OpenSSL 1.x layout

fd = read_using_v1_struct(ssl_ptr)

if (fd_exists_in_connection_map(fd))

return fd // Success!

// Try OpenSSL 3.0 layout

fd = read_using_v3_0_struct(ssl_ptr)

if (fd_exists_in_connection_map(fd))

return fd

// Try OpenSSL 3.2 layout

fd = read_using_v3_2_struct(ssl_ptr)

if (fd_exists_in_connection_map(fd))

return fd

// Try OpenSSL 3.5 layout

fd = read_using_v3_5_struct(ssl_ptr)

if (fd_exists_in_connection_map(fd))

return fd

return INVALID // Couldn't extract FD

}The key: We validate each extracted FD against our connection tracking map (populated by TCP tracepoints). If the FD exists and matches the process ID, we know we used the correct structure.

This prevents false positives from random memory values that happen to look like valid FDs (e.g., reading 0x00000003 from the wrong offset).

Before attaching uprobes, we detect OpenSSL versions from user space:

Step 1: Parse the ELF file

/proc/{pid}/maps → find libssl.so.3

/proc/{pid}/root/usr/lib/libssl.so.3 → open as ELFStep 2: Search the .rodata section

.rodata contains string literals like "OpenSSL 3.0.13"

Regex match: "OpenSSL \d+\.\d+\.\d+"

Step 3: Map to structure version

3.0.x-3.1.x → use ssl_st_3_0

3.2.x-3.4.x → use ssl_st_3_2

3.5.x+ → use ssl_st_3_5Fallback: If version detection fails (custom builds, stripped binaries), use filename heuristics:

.so.3 or .so.3.0 → Assume OpenSSL 3.x

.so.1.1 → Assume OpenSSL 1.1.x

This optimization means we try the correct structure first 95% of the time, avoiding unnecessary validation checks.

Initial implementation: When a new database connection appears, scan /proc/{pid}/maps, find libssl.so, attach uprobes to SSL_read and SSL_write.

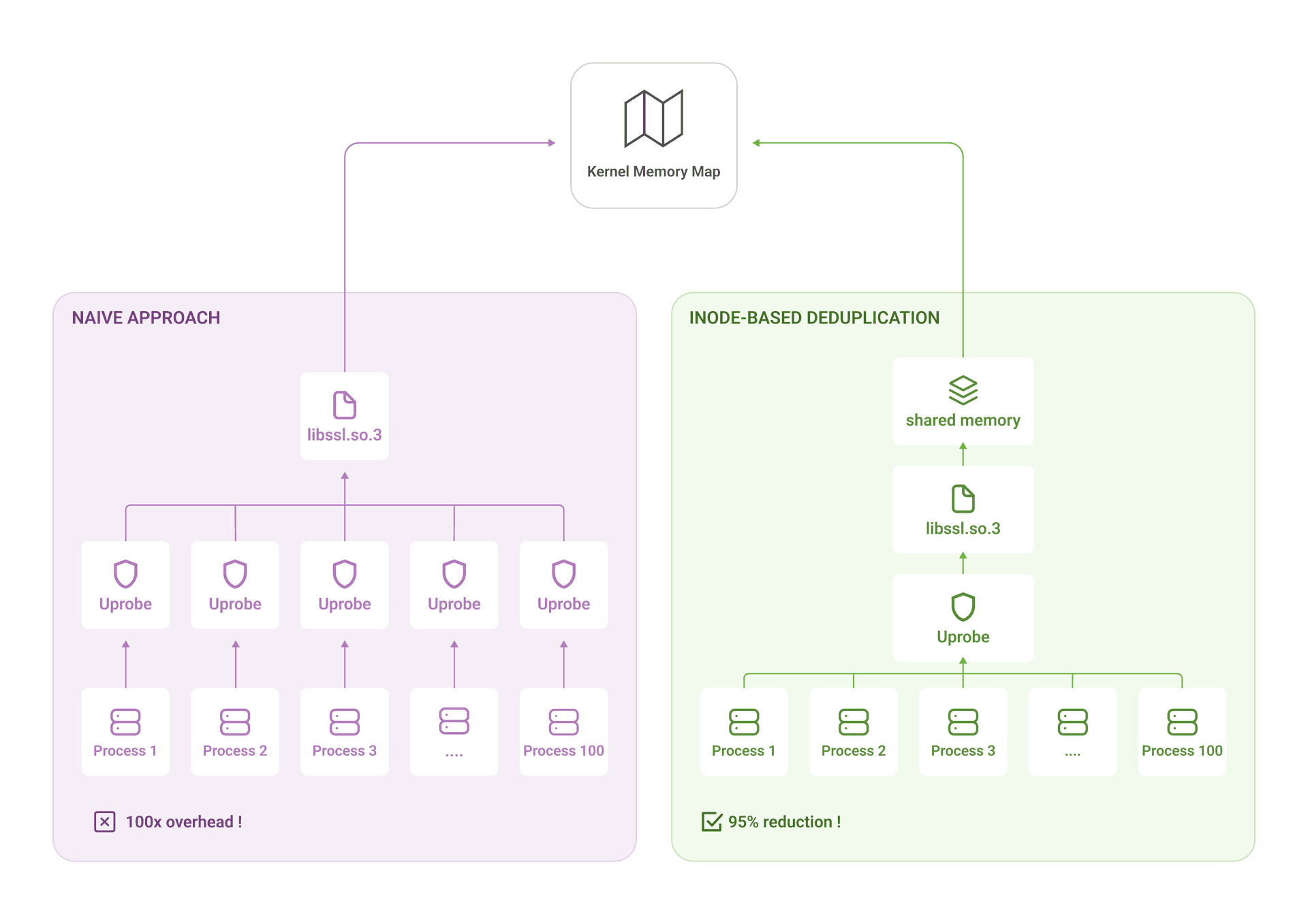

The problem: PostgreSQL has 100 worker processes. All using the same /usr/lib/libssl.so.3 file.

Naively, we'd attach 100 copies of the same uprobe. That's 100 context switches on every SSL read/write call.

The Linux kernel uses memory-mapped files. When 100 processes load the same library, they're all pointing to the same physical memory pages.

That memory region has an inode identifier. If we track by inode instead of PID, we only attach once.

For each new database connection:

1. Find libssl.so in /proc/{pid}/maps

2. Get the inode: stat(/proc/{pid}/map_files/{start_addr}-{end_addr})

3. Check: Have we already attached to this inode?

- Yes → Skip (already monitoring this library)

- No → Attach uprobes, register inodeImpact: This reduced attachment overhead by 95%. Instead of O(processes), we're now O(unique libraries)—typically 2-3 per host.

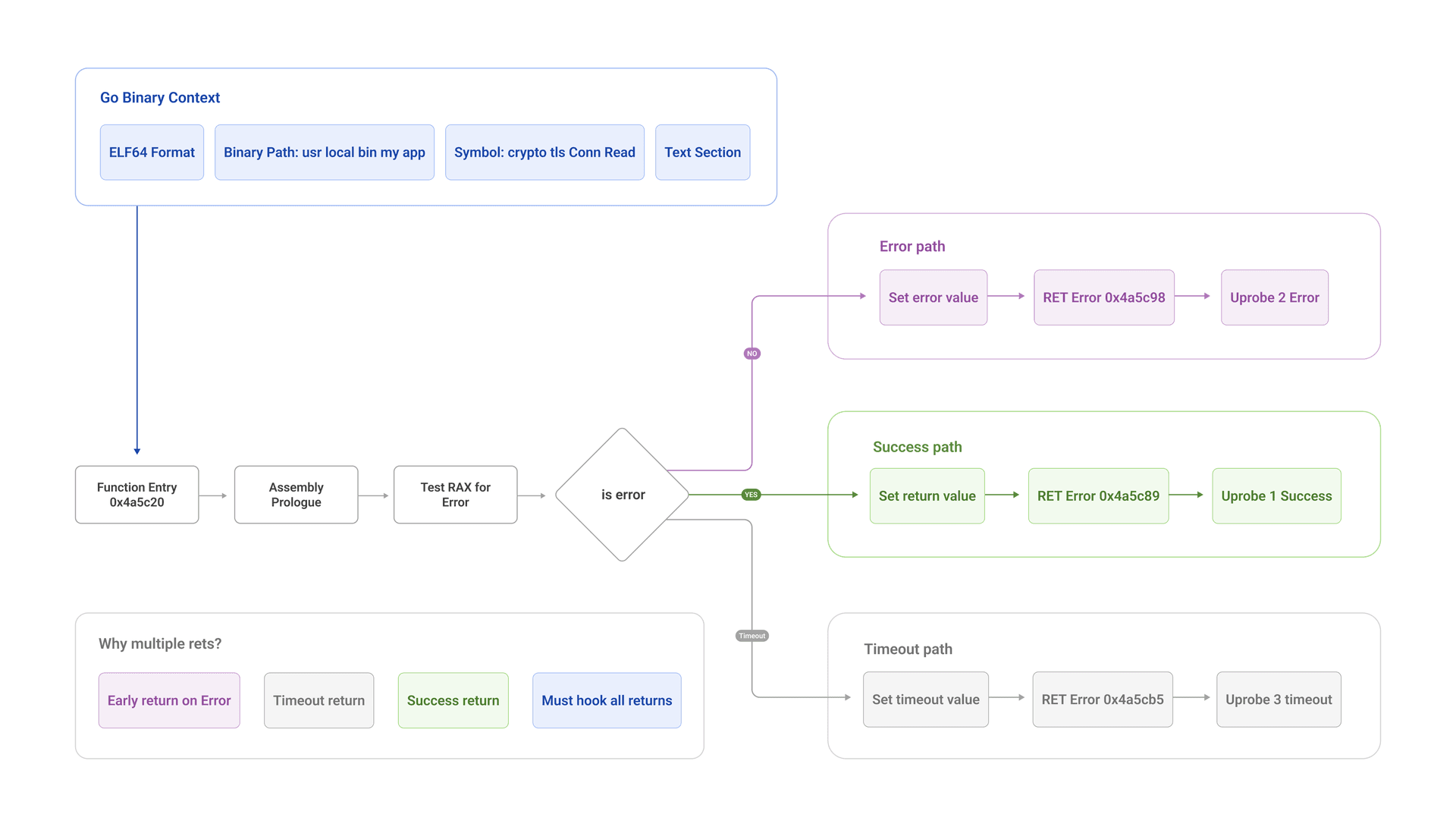

Our OpenSSL hooking worked beautifully. Then we encountered a Go application.

Zero SSL events captured.

Why? Go doesn't use OpenSSL. It has its own crypto/tls implementation in pure Go.

Go's crypto/tls library presents three new problems:

crypto/tls.(*Conn).ReadWe can't hook a library that doesn't exist. We need to hook the binary itself.

Here's what we do:

Step 1: Detect Go binaries

Check ELF file for ".note.go.buildid" section

Parse Go build info to get versionStep 2: Find the crypto/tls.(Conn).Read symbol

Even stripped binaries keep some symbols for runtime

Symbol table contains function boundaries

(See Go's symbol table format: https://pkg.go.dev/debug/gosym)Step 3: Disassemble the function

Read machine code bytes from .text section

Scan for RET instructions (opcode 0xC3 on x86_64)

Record offset of each RETStep 4: Hook every RET instruction

For each RET offset:

Attach uprobe at that address

In probe: extract return value (bytes read) and buffer pointerWe hook every RET because Go's compiler generates multiple return paths, and we need to catch all of them.

Go 1.17+ passes arguments in registers:

buf = PT_REGS_PARM2(ctx) // Second argument (buffer)

ret_len = PT_REGS_PARM1(ctx) // First return value (length)Go <1.17 passes arguments on the stack:

buf = *(stack_pointer + 16)

ret_len = *(stack_pointer + 40)We detect Go version from the binary's build info and use the correct extraction method.

We can't read the plaintext buffer in the entry uprobe because we don't know how many bytes were actually transferred yet.

SSL_write(ssl_ctx, buffer, 4096) ← Requested: write 4096 bytes

... OpenSSL does its thing ...

return 3872 ← Actually written: 3872 bytes

If we read 4096 bytes in the entry probe, we're over-reading by 224 bytes (garbage data). This wastes ring buffer space and can crash if the buffer is shorter than requested.

Entry probe (saves state):

uprobe__SSL_write(ssl_ctx, buffer_ptr, requested_len) {

// Save buffer pointer for later

saved_state = {

buffer: buffer_ptr,

ssl_ctx: ssl_ctx

}

map.store(thread_id, saved_state)

}

Return probe (reads actual data):

uretprobe__SSL_write(actual_bytes_written) {

saved_state = map.lookup(thread_id)

if (actual_bytes_written <= 0) {

return // Write failed

}

// Now read exactly the bytes that were written

read_buffer(saved_state.buffer, actual_bytes_written)

map.delete(thread_id)

}This ensures we only capture the exact bytes that were successfully transmitted.

After solving all these challenges, we deployed across customer environments.

Our implementation handles:

This covers 95%+ of production database configurations we encountered across customers.

The system is designed to never break existing database operations:

We never go completely blind, and we never cause outages.

Chrome and many Google services use BoringSSL, which has different internal structures. We'd need to:

Rust's rustls library is gaining adoption, especially in Rust-native services. Challenges:

QUIC runs TLS 1.3 over UDP instead of TCP. Our connection tracking assumes TCP sockets with file descriptors. We'd need:

Building production-grade SSL tracing taught us that the hard part isn't the eBPF—it's handling the diversity of crypto implementations in real environments.

The techniques that made this work:

For Aurva, this gives us visibility into encrypted database traffic without certificates, proxies, or application changes—exactly what data security monitoring requires.

And most importantly: it works in production, at scale, without breaking anything.

If you're building security or observability tools, SSL/TLS encryption is not optional—it's the default state of production systems.

Traditional approaches (MITM proxies, audit logs, application instrumentation) all fail for different reasons. eBPF uprobes offer a path forward, but only if you handle the complexity of real-world crypto libraries.

The devil is in the details: version detection, structure fallbacks, inode deduplication, ABI differences. Get any one of these wrong, and you have silent data loss.

Get them all right, and you can finally see what's happening in your encrypted database traffic.

USA

AURVA INC. 1241 Cortez Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA - 94086

India

Aurva, 4th Floor, 2316, 16th Cross, 27th Main Road, HSR Layout, Bengaluru – 560102, Karnataka, India

PLATFORM

Access Monitoring

AI Security

AI Observability

Solutions

Integrations

USA

AURVA INC. 1241 Cortez Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA - 94086

India

Aurva, 4th Floor, 2316, 16th Cross, 27th Main Road, HSR Layout, Bengaluru – 560102, Karnataka, India

PLATFORM

Access Monitoring

AI Security

AI Observability

Integrations

USA

AURVA INC. 1241 Cortez Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA - 94086

India

Aurva, 4th Floor, 2316, 16th Cross, 27th Main Road, HSR Layout, Bengaluru – 560102, Karnataka, India

PLATFORM

Access Monitoring

AI Security

AI Observability

Integrations