Platform

AI Security

AI Security

AI Observability

Solutions

Integrations

Resources

When your eBPF program is bottlenecked not by your code, but by how you prove it's safe

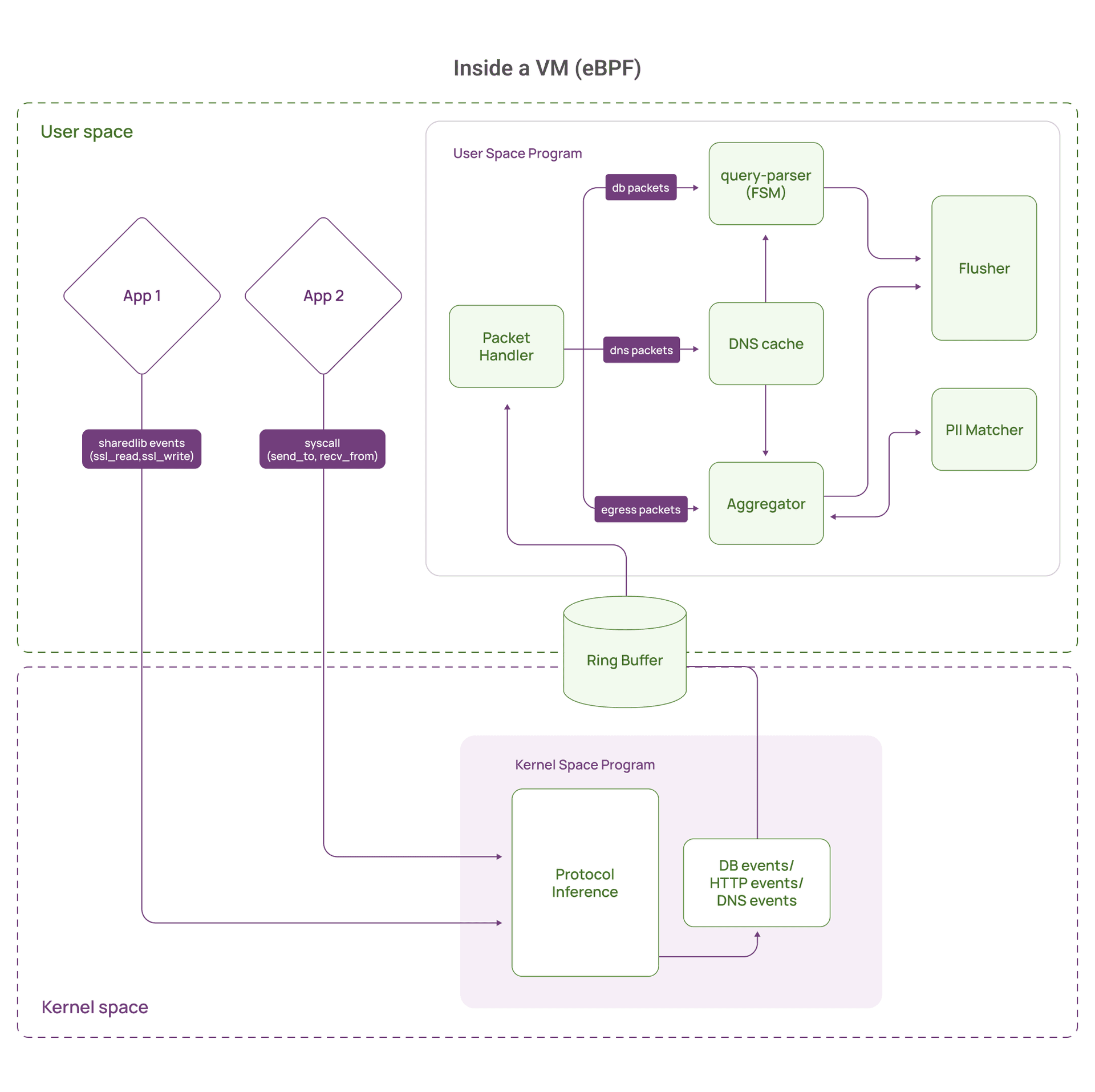

Our platform captures database queries in real-time for security monitoring: tracking who's accessing what data, auditing sensitive data access, and even detecting SQL injection attempts. We use eBPF to intercept database traffic at the kernel level, which gives us several advantages:

Our eBPF program monitors low-level system calls like sendto() and recvfrom(), as well as SSL/TLS functions, to capture database traffic directly in the kernel. It collects all the raw data passing through, along with context such as process ID, connection details, and timestamps. This raw stream is then sent to userspace, where we parse it into full database queries and associated metadata, like the number of columns and rows returned.

This works beautifully, but it comes with its own set of engineering challenges.

We hit a wall during load testing.

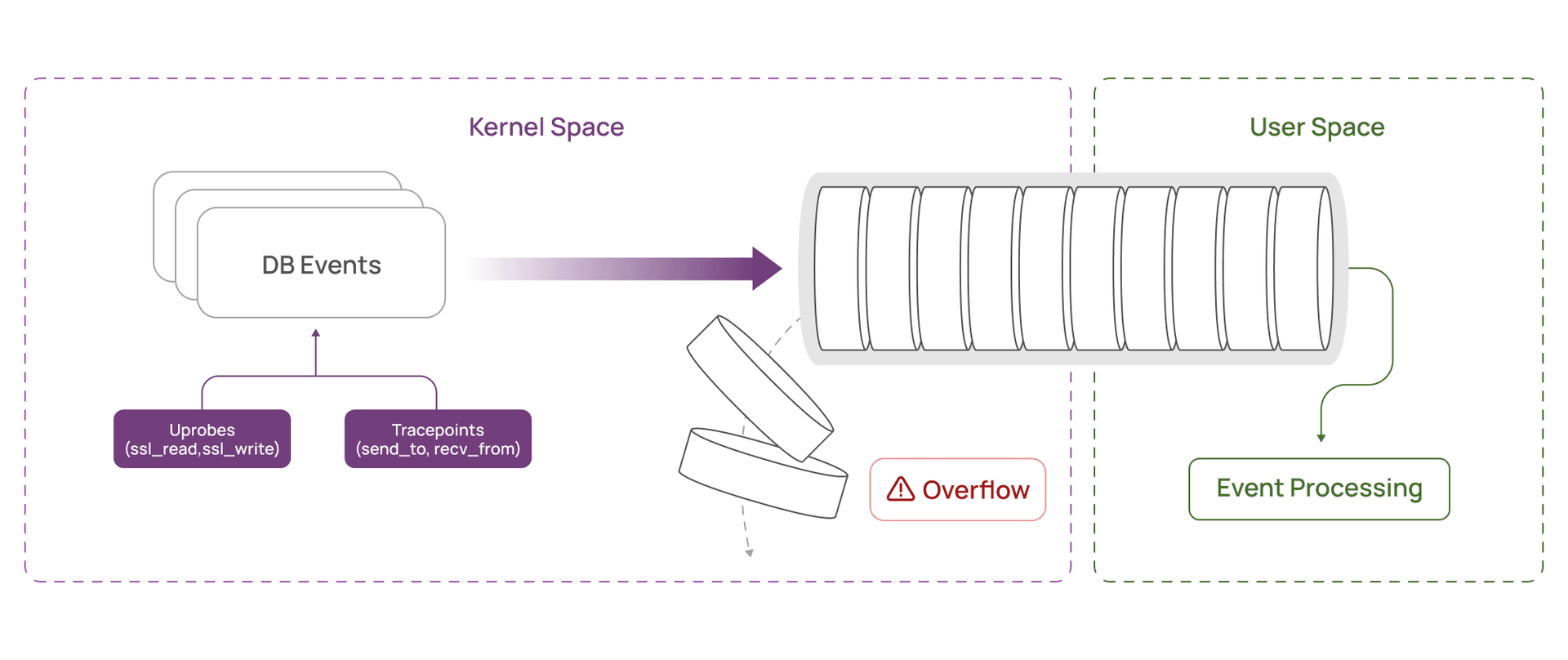

Our setup was simple. On a VM running a load test application, we tested our collector, a lightweight eBPF-based agent, against a MySQL database running with SSL/TLS enabled. Everything worked until we reached around 500 to 600 queries per second. At that point, packet loss spiked suddenly and severely.

The ring buffer, a fixed-size queue used to move data from the kernel to user space, was filling faster than it could be drained. Once full, captured traffic was dropped.

What made this puzzling was the contrast with non-SSL traffic. The same database, running the same queries without SSL, handled over 5,500 QPS without issue. No packet loss. No elevated CPU usage.

With SSL enabled, CPU usage crossed two cores at just 500-600 QPS. Memory looked fine, and Prometheus showed normal latency across all processing stages. That ruled out our parsing and analysis logic.

The problem was earlier. The bottleneck was in how we were capturing data inside the kernel and pushing it to user space.

We added custom instrumentation to track exactly what was filling the ring buffer. That's when we saw it: we were sending an absurd number of tiny events.

Here's what was happening. When you query a MySQL database over SSL, the response doesn't arrive as one clean packet. It comes fragmented: large result sets get split across multiple sendto() or recvfrom() syscalls

In our test scenario, a typical MySQL SSL response fragment was 4 to 40 bytes. Sometimes smaller. These are tiny things like:

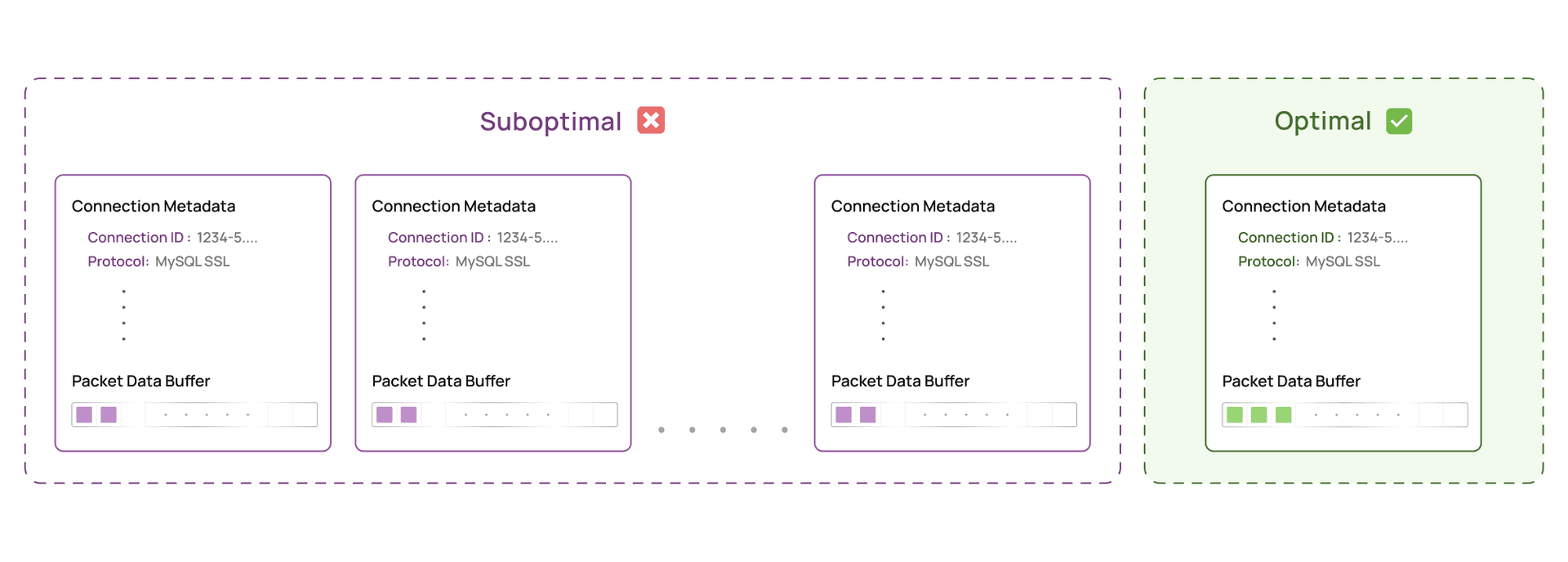

But here’s the problem. For every single fragment, we were sending an event consisting of:

So a 20-byte response fragment ended up reserving 1,224 bytes in the ring buffer. That’s a 6,000% overhead.

Now imagine a large query result split into 100 fragments. We were sending 100 separate events, each with full metadata, each reserving a full 1KB buffer. The ring buffer, designed to handle thousands of events, was bloating with mostly empty space.

At 500-600 QPS with fragmented responses, we were pushing tens of megabytes per second into the ring buffer, 95% of which was wasted padding.

The fix seemed straightforward: accumulate small fragments in kernel space before sending them to user space.

Instead of sending every 20-byte fragment immediately with full metadata, we could:

Think of it like packing boxes for shipping. You don't send 100 separate boxes each containing one screw. You pack 100 screws into one box and ship it once.

For our use case:

100× reduction in ring buffer traffic. Problem solved, right?

Not quite.

In eBPF, you don't just write correct code. You write code that the verifier can prove is safe. The verifier is a component of the Linux kernel that inspects every eBPF program before it runs. Its job is to make sure the program can’t crash the kernel, access memory it shouldn’t, or run forever. It checks things like memory safety, pointer usage, and loops. If the verifier isn’t convinced the program is safe, it simply won’t let it run. And the verifier is notoriously strict.

Here's the problem. To accumulate fragments, you need to do something like this:

accumulation_buffer[current_offset] = fragment_data

current_offset += fragment_sizeIn actual eBPF code, this looks like:

bpf_probe_read_user(&buffer[offset], size, source_ptr);The verifier needs to prove that offset + size will never exceed the buffer bounds. If it can't prove this at compile time, it rejects your program, even if your logic is correct.

The verifier's limitation boils down to this: it cannot track relationships between variables.

Let's say you have:

offset (A) – where you're writing in the buffersize (B) – how much you're writingbuffer_capacity – your total buffer sizeYou might write checks like:

if (offset + size < buffer_capacity) {

bpf_probe_read_user(&buffer[offset], size, source);

}This seems safe to a human: "only write if there's space." But the verifier doesn't understand that the if condition guarantees safety. It treats offset and size as independent variables that could be anything.

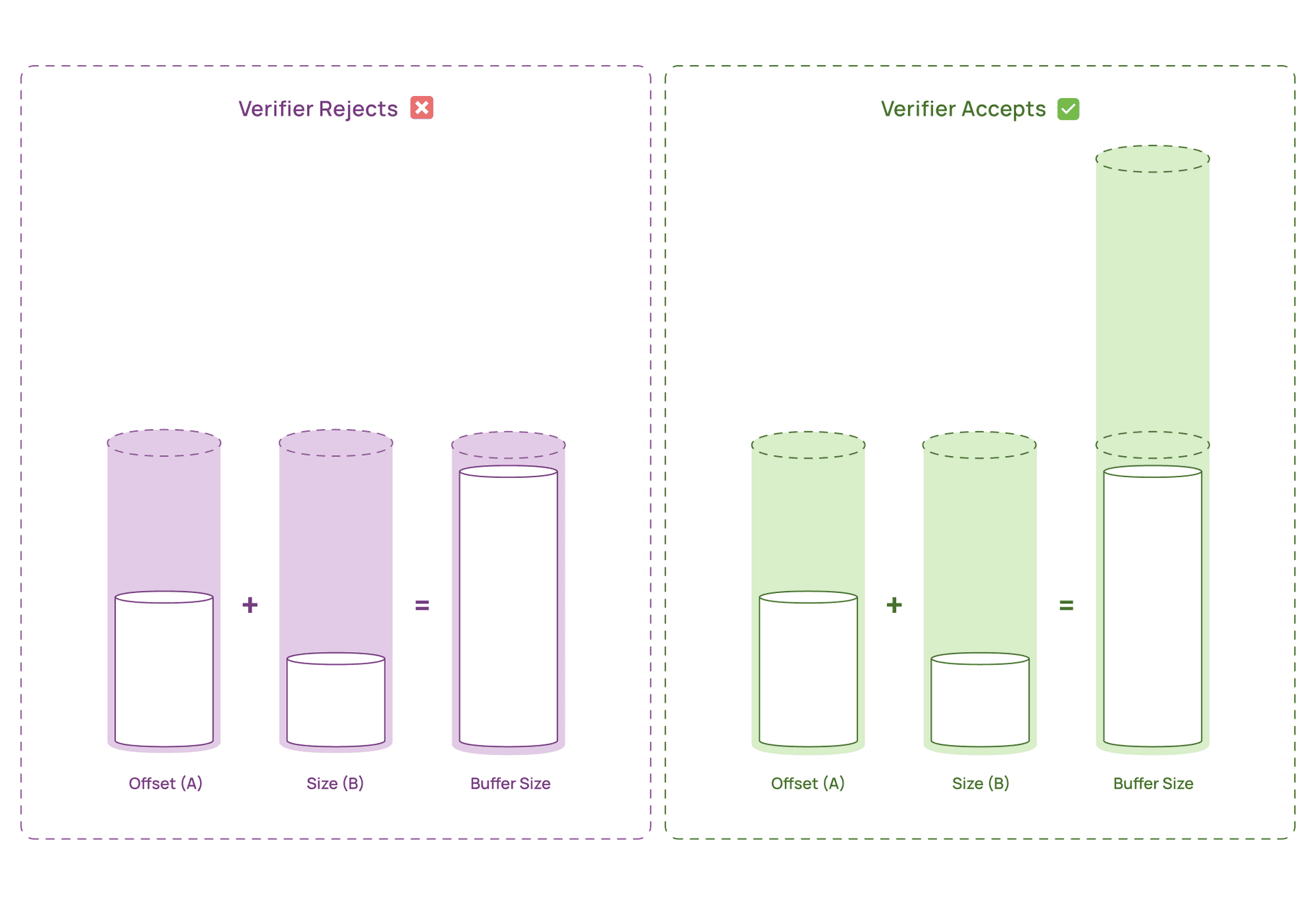

The only way to satisfy the verifier is to make the bounds statically provable, meaning the sum of the maximum possible values of A and B must be less than buffer_capacity, regardless of runtime checks.

This constraint is detailed in this Stack Overflow post, which explains the fundamental limitation: the verifier cannot retain relationships between variables like it does for ctx->data_end in networking programs.

Our first accumulation buffer was 1KB, matching the size we send to userspace in each flush. This seemed logical:

But when we tried to compile it, the verifier rejected it. Why? Because our code had two variable components:

offset (where we're writing) – could be anywhere from 0 to 1023size (how much we're copying) – could be anywhere from 1 to 1024The verifier computes: "worst case, offset = 1023 and size = 1024, so 1023 + 1024 = 2047. But your buffer is only 1024 bytes. Rejected."

Our runtime checks didn't matter. The verifier couldn't trust them.

At this point, it felt like a dead end. The logic was sound and the bounds were checked, yet the verifier still refused to budge. However, this also told us something important: if the verifier’s problem was the worst-case math, then the fix wouldn’t come from more checks, but from changing the shape of the problem itself.

We had two options:

offset and size so their sum always fits in 1KBOption 1 was impractical: We needed the flexibility to handle variable-sized fragments.

Option 2 was counterintuitive but effective: Make the accumulation buffer larger than what we actually use.

We doubled it to 2KB. Now:

offset = 1023, size = 10242047 bytes2048 bytesWe never actually use the full 2KB at runtime. Our logic still fills at most 1KB before flushing. But the extra space exists purely to satisfy the verifier's static analysis.

It felt wasteful; allocating double the memory we need. But at scale, it's negligible. A 2KB per-connection overhead for 10,000 connections is just 20MB of kernel memory. Modern systems have gigabytes. The trade-off was worth it.

We also had to use bit-masking to make array offsets provably safe:

// Instead of:

buffer[offset] = data;

// We use:

buffer[offset & (BUFFER_SIZE - 1)] = data;The mask ensures offset can never exceed BUFFER_SIZE - 1, which the verifier can verify statically. Note that this requires BUFFER_SIZE to be a power of 2 (1024, 2048, 4096, etc.).

At a high level, we maintain a per-connection accumulator in kernel space. Each accumulator holds a snapshot of connection metadata, a small amount of state, and a buffer used to temporarily store data before it is sent to user space.

Per-connection accumulator:

├─ Metadata snapshot (captured once per batch)

│ ├─ Connection ID

│ ├─ Thread ID

│ ├─ Protocol type

│ └─ Traffic direction

├─ Buffer state

│ └─ Current fill level (0 to MAX_FLUSH_SIZE bytes)

└─ Accumulation buffer (2 * MAX_FLUSH_SIZE bytes allocated)In our implementation, MAX_FLUSH_SIZE is 1024 bytes. This is the maximum amount of data we ever send to userspace in a single event. The accumulation buffer is allocated at 2 * MAX_FLUSH_SIZE, or 2048 bytes, not because we need that much data, but because the eBPF verifier requires provable upper bounds on all memory accesses.

When a fragment is captured, we first look up or create the accumulator for that connection. If the stream context has changed, such as thread ID, traffic direction, or protocol state, we immediately flush the accumulated data so that each batch remains context-consistent.

Next, we decide whether the fragment can be accumulated at all. To satisfy the eBPF verifier, we cap how many bytes can be copied into the accumulation buffer in a single step using MAX_ACCUM_COPY_SIZE (set to MAX_FLUSH_SIZE - 2). If the fragment exceeds this limit, or if we are handling a connection close, we flush what we have and send the fragment directly to userspace. This separate copy limit exists specifically because of older kernels like RHEL 8 with kernel 4.18, whose verifier is more conservative and cannot prove safety at the theoretical maximum.

For fragments that can be accumulated, we copy only as much data as will fit into the current flush window. The accumulator tracks how full it is, and once it reaches MAX_FLUSH_SIZE, we flush that data to userspace. Even though the accumulation buffer is larger, we never flush more than this threshold.

When computing where to copy data into the buffer, we mask the current fill level with BUFFER_MASK, which is defined as MAX_FLUSH_SIZE - 1. Since MAX_FLUSH_SIZE is a power of two, this ensures the calculated offset always stays within bounds in a way the verifier can reason about.

Any leftover bytes that do not fit into the accumulator are sent directly to user space.

Here is the corresponding code:

static __always_inline void on_fragment_captured(

void *ctx,

uint64_t connection_id,

const char *fragment,

uint32_t fragment_size,

struct metadata_t *metadata)

{

// Look up accumulator state

struct accumulator_t *accumulator =

bpf_map_lookup_elem(&accum_map, &connection_id);

if (!accumulator) {

bpf_map_update_elem(&accum_map, &connection_id,

&ZERO_ACCUMULATOR, BPF_ANY);

accumulator = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&accum_map, &connection_id);

if (!accumulator)

return;

}

// Flush when stream context changes

if (stream_context_changed(accumulator, metadata)) {

flush_to_userspace(ctx, accumulator, metadata);

update_accumulator_metadata(accumulator, metadata);

}

uint32_t remaining = fragment_size;

// If closing or fragment too large, flush and send directly

if (metadata->source_fn == CLOSE ||

remaining > MAX_ACCUM_COPY_SIZE) {

flush_to_userspace(ctx, accumulator, metadata);

send_to_userspace(ctx, fragment, fragment_size, metadata);

return;

}

// Flush if accumulator is already full

if (accumulator->fill_level >= MAX_CHUNK_SIZE - 1) {

flush_to_userspace(ctx, accumulator, metadata);

}

// Compute available space in the accumulation window

uint32_t space_available =

(MAX_CHUNK_SIZE - 1) - accumulator->fill_level;

// Compute verifier-safe destination offset

uint32_t safe_offset =

accumulator->fill_level & (MAX_CHUNK_SIZE - 1);

// Compute number of bytes we can safely copy

uint32_t bytes_to_copy = space_available;

if (bytes_to_copy > remaining)

bytes_to_copy = remaining & (MAX_CHUNK_SIZE - 1);

// Extra cap required for older kernels (e.g. RHEL 8, kernel 4.18)

if (bytes_to_copy > MAX_ACCUM_COPY_SIZE)

bytes_to_copy = MAX_ACCUM_COPY_SIZE;

// Copy fragment slice into accumulation buffer

bpf_probe_read_user(

&accumulator->buffer[safe_offset],

bytes_to_copy,

fragment

);

accumulator->fill_level += bytes_to_copy;

remaining -= bytes_to_copy;

// Flush once we reach the flush threshold

if (accumulator->fill_level >= MAX_FLUSH_SIZE) {

flush_to_userspace(ctx, accumulator, metadata);

accumulator->fill_level = 0;

}

// If leftover data remains, flush and send it directly

if (remaining > 0) {

flush_to_userspace(ctx, accumulator, metadata);

send_to_userspace(

ctx,

fragment + bytes_to_copy,

remaining,

metadata

);

}

}The key insight is simple: we allocate a 2048-byte accumulation buffer, but flush data to userspace using a separate 1024-byte buffer.

Before this change, we sent a full 1024 byte buffer for every tiny fragment, wasting most of the space. With accumulation, we pack dozens of fragments into a single flush, dramatically reducing ring buffer pressure.

We would have liked to push this further using loops to batch more data, but the eBPF verifier refused to accept that approach.

After deploying kernel-space accumulation:

Throughput:

CPU Utilization:

Memory Usage:

The ring buffer went from overflowing at 500 QPS to handling 5,500+ QPS comfortably. The bottleneck was never our processing logic: it was the sheer volume of tiny, wasteful events we were pumping into the ring buffer.

By accumulating fragments before sending, we turned 100 mostly-empty 1KB events into 1 full 1KB event.

And the CPU improvement? That came from reduced context switches and userspace processing. Every ring buffer event triggers a userspace wakeup. Fewer events = fewer interruptions = better CPU efficiency.

This problem isn’t tied to a single protocol or use case. It appears anytime an eBPF program needs to move many small pieces of data from kernel space to user space.

If you’re using eBPF for:

you can run into the same bottleneck. Fixed per-event overhead adds up fast, and a naive design can hit throughput limits long before CPU or memory become an issue.

To sum it up, the fix wasn’t better parsing or faster SSL handling. It was changing how data crosses the kernel – user space boundary.

We went from ~500 QPS to 5,500+ QPS (a 1000% or 10x improvement) with a single structural change: accumulating small packet fragments in the kernel before flushing to user space. Previously, every tiny fragment carried full metadata and an almost empty 1KB buffer, quickly bloating the ring buffer under load. Accumulation amortized that fixed cost and removed the bottleneck.

We knew early that accumulation was the right approach. What nearly stopped us was the eBPF verifier. A 1KB accumulation buffer was logically correct, but the verifier couldn’t prove the bounds. The breakthrough was pragmatic: over-allocate a 2KB buffer so the verifier can prove safety, while still flushing only 1KB at runtime.

The lesson is simple: in eBPF, correctness alone isn’t enough. Your data layout and control flow must match what the verifier can reason about. Once we designed for that constraint, kernel-side accumulation worked as intended and unlocked the performance we were missing all along.

And if we had given up at that point? Well… I guess we’ll never know.

Thanks for reading. If you're building eBPF-based observability tools, we hope this saves you the two days of head-scratching we went through. Feel free to reach out with questions or your own verifier war stories.

USA

AURVA INC. 1241 Cortez Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA - 94086

India

Aurva, 4th Floor, 2316, 16th Cross, 27th Main Road, HSR Layout, Bengaluru – 560102, Karnataka, India

PLATFORM

Access Monitoring

AI Security

AI Observability

Solutions

Integrations

USA

AURVA INC. 1241 Cortez Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA - 94086

India

Aurva, 4th Floor, 2316, 16th Cross, 27th Main Road, HSR Layout, Bengaluru – 560102, Karnataka, India

PLATFORM

Access Monitoring

AI Security

AI Observability

Integrations

USA

AURVA INC. 1241 Cortez Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA - 94086

India

Aurva, 4th Floor, 2316, 16th Cross, 27th Main Road, HSR Layout, Bengaluru – 560102, Karnataka, India

PLATFORM

Access Monitoring

AI Security

AI Observability

Integrations